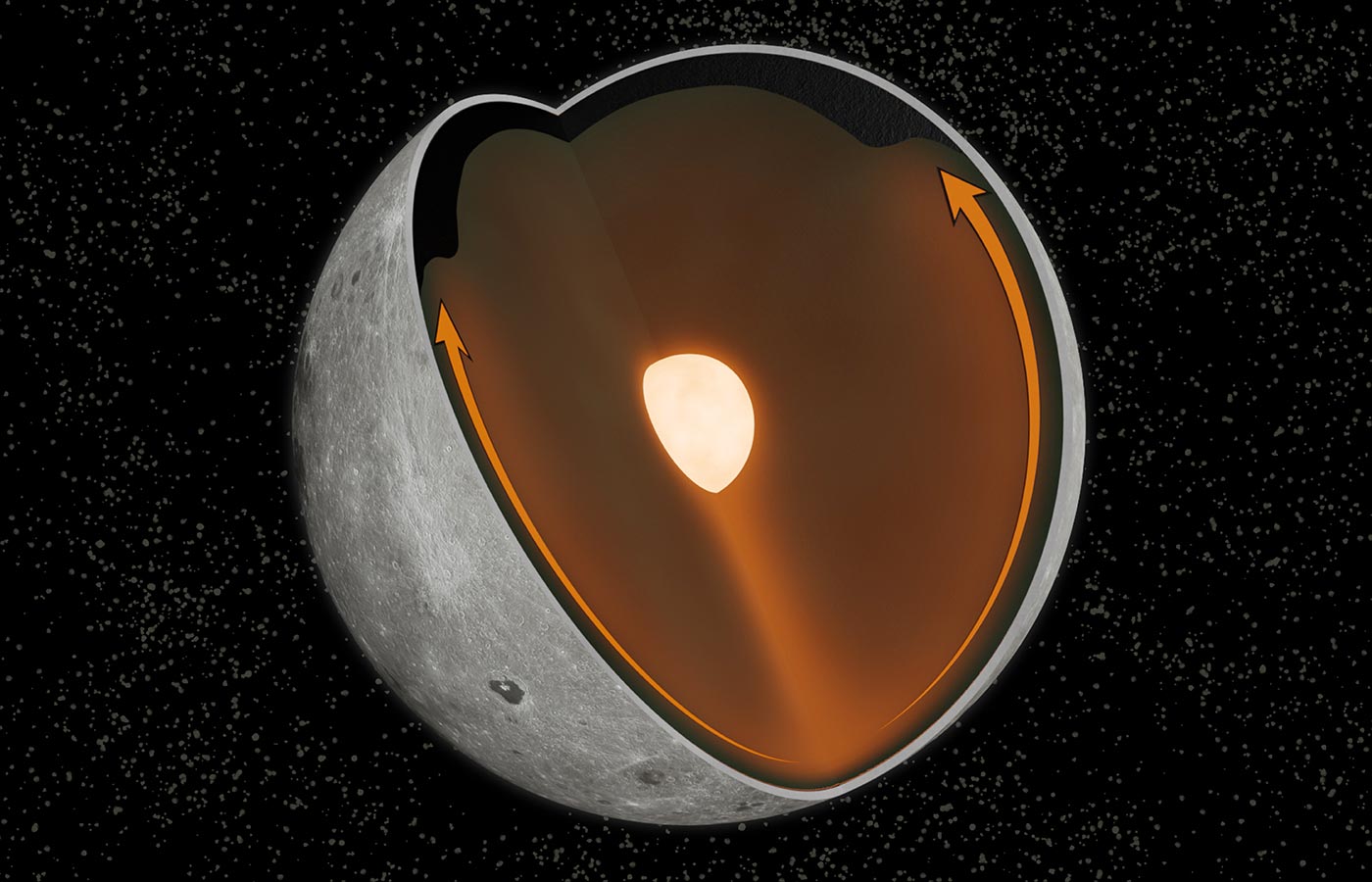

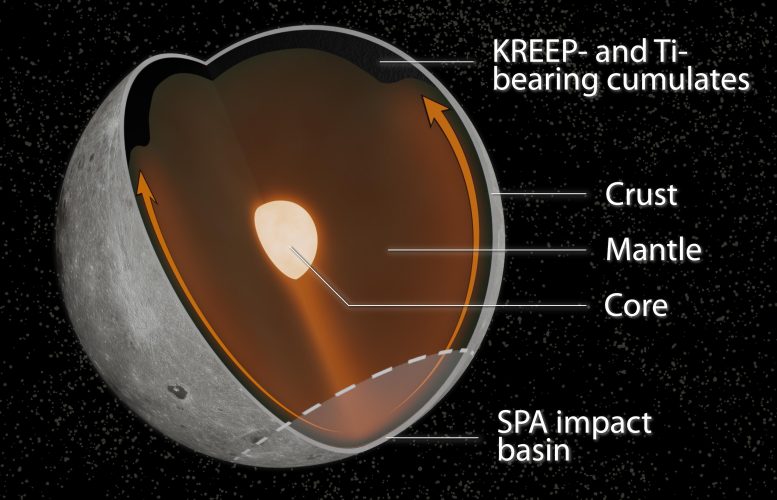

Un nuovo studio rivela che un’antica collisione sul polo sud della luna ha alterato i modelli di convezione nel mantello lunare, concentrandosi su un gruppo di elementi che producono calore sul lato vicino. Questi elementi hanno giocato un ruolo nella formazione del vasto ferro di cavallo lunare visibile dalla Terra. Credito: Matt Jones

Una nuova ricerca mostra come l’impatto del Polo Sud della Luna-bacino di Aitken sia correlato al netto contrasto nella composizione e nell’aspetto tra i due lati della Luna.

La faccia che la Luna mostra alla Terra sembra molto diversa da quella che nasconde sul lato opposto. Il lato vicino è dominato dai persiani lunari: i vasti resti di colore scuro di antiche colate laviche. D’altra parte, il lato opposto, pieno di crateri, è praticamente privo di ampie caratteristiche di cavalla. La ragione della grande differenza tra le due parti è uno dei misteri più duraturi della luna.

Ora, i ricercatori hanno una nuova spiegazione per la luna a due facce, una spiegazione correlata a un gigantesco impatto miliardi di anni fa vicino al polo sud della luna.

Un nuovo studio pubblicato su Science Advances mostra che l’impatto che ha formato il gigantesco bacino lunare del Polo Sud-Aitken Basin (SPA) avrebbe creato un enorme pennacchio di calore che si diffondeva all’interno della luna. Questo pennacchio avrebbe contenuto alcuni materiali – una combinazione di terre rare ed elementi che producono calore – così come la vicina luna. Questa concentrazione di elementi potrebbe aver contribuito all’attività vulcanica che ha portato alla creazione delle vicine pianure vulcaniche.

Ampi depositi vulcanici dominano il lato più vicino della Luna (a sinistra), mentre il lato più lontano (a destra) ne contiene molto meno. Il motivo della grande differenza tra le due parti è il mistero della luna perpetua. Credito: Brown University

“Sappiamo che grandi impatti come quello che ha plasmato la SPA creeranno molto calore”, ha affermato Matt Jones, Ph.D. Candidato alla Brown University e autore principale dello studio. La domanda è come questa temperatura influenzi la dinamica interna della Luna. Quello che mostriamo è che in qualsiasi condizione ragionevole al momento della formazione della ZPS, finisce per concentrare questi elementi che producono calore sul lato vicino. Ipotizziamo che ciò abbia contribuito allo scioglimento del mantello che ha portato ai flussi di lava che vediamo in superficie. “

Lo studio è nato dalla collaborazione tra Jones e il suo consulente, Alexander Evans, un assistente professore alla Brown University, insieme a ricercatori della Purdue University, del Lunar and Planetary Science Laboratory in Arizona, della Stanford University e[{” attribute=””>NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

A new study reveals that an ancient collision on the Moon’s south pole changed patterns of convection in the lunar mantle, concentrating a suite of heat-producing elements on the nearside. Those elements played a role in creating the vast lunar mare visible from Earth. Credit: Matt Jones

The differences between the near and far sides of the Moon were first revealed in the 1960s by the Soviet Luna missions and the U.S. Apollo program. While the differences in volcanic deposits are plain to see, future missions would reveal differences in the geochemical composition as well. The nearside is home to a compositional anomaly known as the Procellarum KREEP terrane (PKT) — a concentration of potassium (K), rare earth elements (REE), phosphorus (P), along with heat-producing elements like thorium. KREEP seems to be concentrated in and around Oceanus Procellarum, the largest of the nearside volcanic plains, but is sparse elsewhere on the Moon.

Some scientists have suspected a connection between the PKT and the nearside lava flows, but the question of why that suite of elements was concentrated on the nearside remained. This new study provides an explanation that is connected to the South Pole–Aitken basin, the second largest known impact crater in the solar system.

For the study, the researchers conducted computer simulations of how heat generated by a giant impact would alter patterns of convection in the Moon’s interior, and how that might redistribute KREEP material in the lunar mantle. KREEP is thought to represent the last part of the mantle to solidify after the Moon’s formation. As such, it likely formed the outermost layer of mantle, just beneath the lunar crust. Models of the lunar interior suggest that it should have been more or less evenly distributed beneath the surface. But this new model shows that the uniform distribution would be disrupted by the heat plume from the SPA impact.

According to the model, the KREEP material would have ridden the wave of heat emanating from the SPA impact zone like a surfer. As the heat plume spread beneath the Moon’s crust, that material was eventually delivered en masse to the nearside. The team ran simulations for a number of different impact scenarios, from dead-on hit to a glancing blow. While each produced differing heat patterns and mobilized KREEP to varying degrees, all created KREEP concentrations on the nearside, consistent with the PKT anomaly.

The researchers say the work provides a credible explanation for one of the Moon’s most enduring mysteries.

“How the PKT formed is arguably the most significant open question in lunar science,” Jones said. “And the South Pole–Aitken impact is one of the most significant events in lunar history. This work brings those two things together, and I think our results are really exciting.”

Refernece: “A South Pole–Aitken impact origin of the lunar compositional asymmetry” by Matt J. Jones, Alexander J. Evans, Brandon C. Johnson, Matthew B. Weller, Jeffrey C. Andrews-Hanna, Sonia M. Tikoo and James T. Kean, 8 April 2022, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abm8475